Lakes Above the Clouds

When I was offered the opportunity to carry out my Master’s research project on high altitude lakes in Ecuador, I immediately got excited. The idea of travelling to a beautiful tropical country and doing fieldwork above 4000 meters captivated both the curiosity-driven ecology student and the photographer in me. The experiences, however, even exceeded my expectations.

Our small research team set out to sample as many lakes in the Andes as possible within the two and a half months we were there. We wanted to know what kind of creatures live in tropical mountain lakes and if there are any differences between the lakes that could be used to categorise them.

The climate of the tropical Andes is relatively constant without the seasonal changes that occur in temperate regions. Because of the high altitude the temperature is low and it’s often windy. In addition, the precipitation is high and creates really humid and wet conditions. The grassy landscape is dotted with lakes, wetlands and small streams, even the soil is very moist.

The flora and fauna of the páramo, the tropical mountain grassland is quite fascinating. The vegetation consists mostly of short-growth plants like shrubs and cushion plants. But you can come across patches of paper-tree (Polylepis) thriving at elevations, where no other tree could grow. The páramo is also home to a range of birds including ducks, hummingbirds, wading birds, the caracara (left) and the threatened Andean condor. If you are lucky, you may see some deer coming to the lakes to drink or the vicuñas in Chimborazo National Park. Other species like rabbits, tapirs and spectacled bears also live in these areas, but are very shy.

So why should we care about some lakes in such remote areas? Well, one reason is scientific curiosity and progress. We know so much about the water bodies in Europe and North America, while tropical lakes especially at high altitudes have been somewhat neglected. It is in itself interesting to know what these ecosystems look like under a different climate and altitude. But more importantly, the tropical Andes are predicted to be greatly affected by climate change.

Most of the world’s tropical glaciers are in South America, but they might disappear by the end of the century. Glaciers supply water not only to the páramo and the associated ecosystems, but they are the main source of drinking water.

As glaciers are retreating, new lakes are forming in front of them. As you go up in elevation you find younger and younger lakes. This provides an exciting opportunity to compare the biota of newly formed, glacially influenced and the older lakes.

We found that indeed the lakes that receive melt water from the glacier are different from the ones that do not. You can see on the picture above that this melt water looks creamy white compared to groundwater due to the glacial flour and silt. In such environment plants and animals don't cope well. In addition, the glacial lakes are at higher altitudes, therefore are colder and get stronger UV radiation. Finally, they are younger and it takes a long time until species get established in a newly formed lake. So it is not surprising that we found very few species of water plants, phytoplankton, zooplankton and aquatic insects in these lakes compared to the páramo lakes that are not connected to a glacier.

We can just guess that with time glacial lakes will turn into páramo lakes as the glaciers disappear and the whole landscape changes. What would it mean for biodiversity? Would there be species lost forever? And how would it affect us, humans?

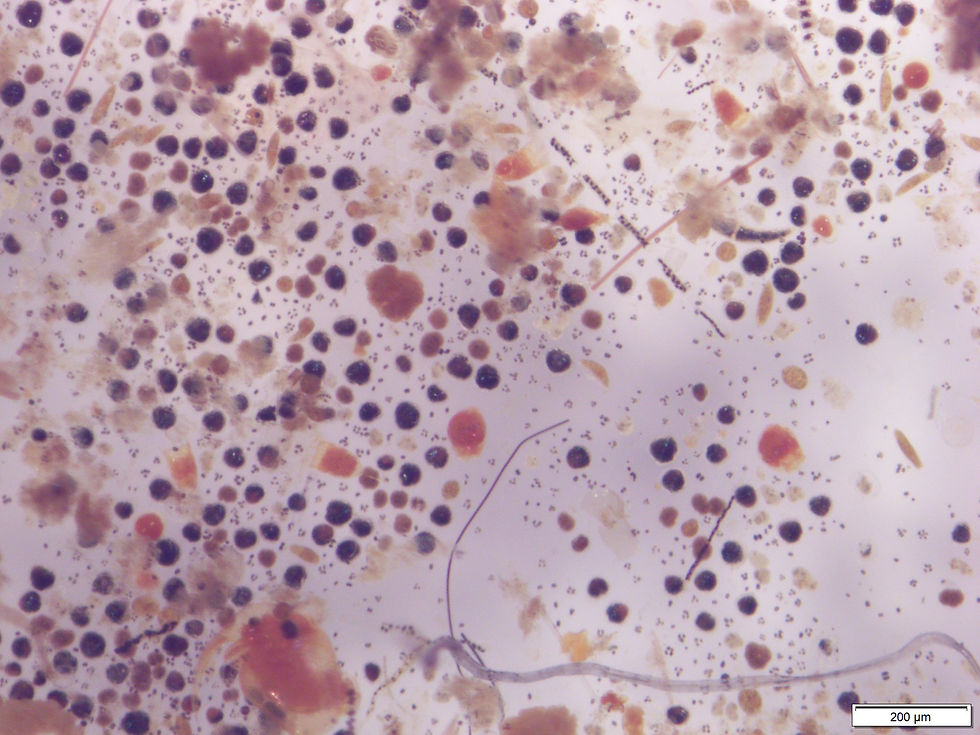

Here's a glimpse of what microscopic organisms live in the lakes:

Phytoplankton is the microscopic ‘plant’ part of aquatic ecosystems. They come in all shapes and sizes, and belong to many different groups. They all photosynthesise and provide the basis for many ecosystems. Some are solitary, while others form long filaments or colonies.

Dinobryon belongs to the group called Golden Algae. They are, like other phytoplankton, microscopic and live in colonies. You can see many cells attached to each other with their sheets. Diatoms are a separate group. They have a case made of two parts and are bilaterally or radially symmetrical.

Copepods are part of the zooplankton, microscopic animals floating in the watercolumn. They feed on phytoplankton and other organic particles in the water. The brownish colour of most samples is due to the lugol used to preserve them, but in this case copepods had a natural bright orange/pink colouration.

Phytoplankton are everywhere from oceans to puddles, in tropical lakes and even on glacial ice. They have global importance as they produce more oxygen than terrestrial plants and support most aquatic foodwebs.

These are single-celled organisms, more animal than plant like. Vorticella belongs to the group Ciliates. You can see the cilia on top of the 'bell' and the contracted, spring-like stalk.

Among the phytoplankton there are rotifers, the tiny bell-shaped animals. They feed on algae and dead organic matter helping decomposition and nutrient cycling.

The tiny copepods belong to the group Crustacea and related to crabs and shrimps. They are the food source for animals higher up in the food chain like fish.

Daphnia is also part of the zooplankton. It's common in aquatic ecosystems and even sold as aquarium fish feed.

Bosmina is another genus of zooplankton, similar to Daphnia. We found them in one of our lakes in extreme density.

Tardigrades are one of the most fascinating organisms on the planet. They can survie extremely low and high temperatures, radiation, drying, freezing and even a space trip!

Tardigrades have eight legs and they are commonly known as 'water bears'. Photo credit:Prof. Reinhardt M. Kristensen

On this close-up ou can see the head and 'brain' of the tardigrade. Photo credit:Prof. Reinhardt M. Kristensen

While doing fieldwork is exciting and a lot of fun, it can also be physically demanding. After a long day in the rain when you’re fingers are so cold that you cannot open a ziplock bag or spent hours climbing with all the equipment on your back to reach the lake at 5000 meters, the only thing you can really think of is a nice, relaxing bath. Not to mention adjusting to high altitude, getting stuck in the swamp up to waist height or looking for lakes in the dense fog ...

You can read our article here:

Barta, B., Mouillet, C., Espinosa, R. et al. Hydrobiologia (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3428-4